C. Files

Read time: 14 minutes

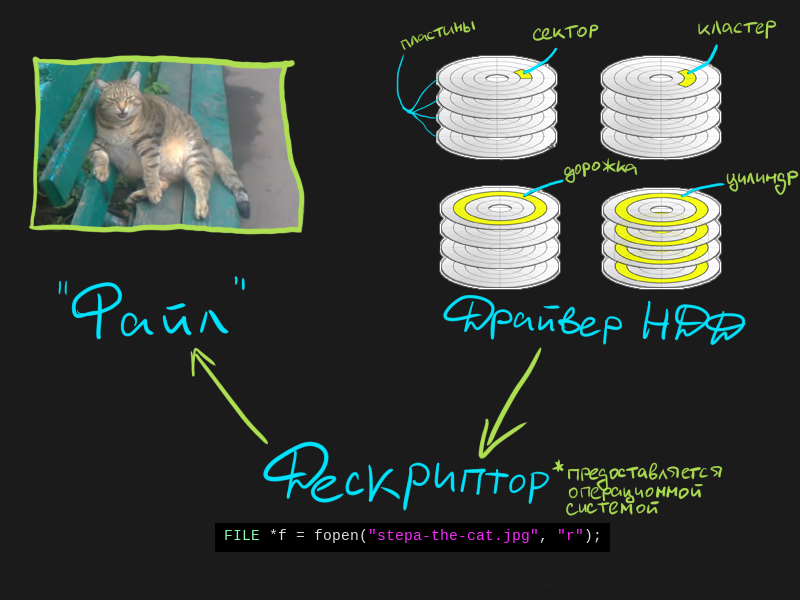

A file (file) is an abstraction supported by the operating system that allows you to work with data recorded on external media (magnetic recording on a hard disk, flash memory on an SSD or flash drive).

Thus, when working with files, we work with the operating system, which, in turn, works with physical device drivers.

I’m oversimplifying what’s going on there - if you want to understand how it actually works, you can read E. Tannenbaum “Operating Systems”, chapter “File Systems”.

In the picture, between the file and the driver, I indicated a certain descriptor.

Descriptor – an identifier provided by the operating system, when specified, it is possible to perform read / write operations to a specific file.

And how to make these read/write operations? First you need to open the file.

A description of ALL the functions that I will use here can be found [here] (https://www.cplusplus.com/reference/cstdio/) or in any other part of the Internet.

Open file

fopen is a function that calls the operating system to obtain a handle to a file with the given name. In addition to the file name, you must specify the mode of working with it.

FILE *f = fopen("some-file.txt", "r");

File name

The file is always searched for in the folder from which the program was launched. If you need to specify a file located in another folder, then you need to specify it using an absolute or relative path.

-

Absolute (full) path: “D:/some-folder/some-file.txt” – indicating the drive and all folders

-

Relative path: “../some-folder/some-file.txt” – using the symbol “..” you can go up one level (exit the current folder). Usually used if the required file is located on the same drive in the adjacent / parent folder. You can use as many “..” characters as you need: “../../../../some-file.txt”

Knowing about absolute and relative paths will be useful to you in any language and any operating system - remember this.

File mode

There are 3 main modes in total:

- “r” – reading. Open an existing file and read data from there.

- “w” is a record. We create a new file (if one already exists, then overwrite it) and write the data there.

- “a” – write to the end. Open an existing file (if the file doesn’t exist yet, create it) and write the data to the end of the file.

These modes can be appended with a “+” to unlock readability for “w” and “a”, and writeability for “r”.

Here is the table in which I collected all the combinations

| Mode | Reading | Entry | Create a new file (if not) | Clear content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “r” | + | - | - | - |

| “w” | - | + | + | + |

| “a” | - | + | + | - |

| “r+” | + | + | - | - |

| “w+” | + | + | + | + |

| “a+” | + | + | + | - |

They do not need to be memorized - usually everyone uses:

- “r” when reading

- “w” in entries

- “r+” when reading/writing

But if in some situation you need something else, feel free to experiment.

Close the file

fclose – the function accepts an open file descriptor, and closes it, writing all the data from the buffer.

fclose(f);

Wait, what’s a buffer?

FILE is not a handle

I was not completely honest when I said that FILE is a file descriptor. In fact, FILE is a wrapper around a real handle.

To get the real handle, depending on the operating system, you need to use the following functions:

The FILE descriptor wrapper supports:

- Buffering - that is, it does not immediately write all the data to the file, but waits until a sufficient amount of data has accumulated in a temporary buffer (which is stored in RAM)

- Position tracking – thanks to this, we can conveniently find out if we have reached the end of the file when reading

- Error handling – you can find out if an error occurred while performing a read/write using the [ferror] function (https://www.cplusplus.com/reference/cstdio/ferror/)

You can read more about the difference between a FILE and a descriptor here.

Close FILE

Okay, we figured out the closing of FILE - when closing, a buffer is written to the file.

When to do it? When finished with the file.

What happens if this is not done?

If the program exits normally, then nothing bad will happen – before closing, our program will write the buffer to a file and close the file descriptor.

If the program crashes before closing FILE, nothing will be written to the file, since the buffer did not have time to write to the file. However, the handle will be closed, not by the program, but by the operating system (because the program that received it has died). Here is an example of such a situation:

#include <stdio.h>

int main()

{

char *text = "Some text to fill the file\nAnd some more text";

FILE *f = fopen("some-file.txt", "w");

// Write text to FILE

fprintf(f, "%s", text);

char *x = NULL;

// Refer to null pointer (fall)

*x = 1;

// We don't get to closing the file, and the file remains empty. we opened it with "w"

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

If we closed the file before the fall, then everything would be fine in this case. In general - always follow the closure.

You can write the buffer to the file before closing with the fflush function. If I would call it before the crash in the program above, then the data would be written to the file.

Read/write to file

There are a number of functions in the “stdio.h” library for writing to a file:

- fprintf – write text to a file, specifying a format string (as in normal printf)

- fputc – write one char to file

- fputs – write a string (everything up to ‘\0’) to a file

- fwrite – write an array of values (with the specified element size and number of elements) to a file

For the record, there are alter egos of the same functions:

- fscanf – read text from a file, specifying a format string (as in normal scanf)

- fgetc – read one char from file

- fgets – read a line from a file. Everything is read up to the end of the file or the line break character ‘\n’. The line break character is included in the resulting string

- fread – read an array of values (with the specified element size and number of elements) from a file

Let me write a program that “encrypts” all the characters in a file and then “decrypts” them.

“Encryption” will be the offset of the character code by 1, and “decryption” will be the offset of the character code by -1.

In this case, there will be a necessary condition - the character ‘0’ must be at the beginning of the file.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

FILE *f = fopen("some-file.txt", "r+");

if(f == NULL)

{

printf("Can't open file");

return 0;

}

// If the first character is 0 - the file is decrypted, and if 1 - it is encrypted

char is_encrypted = fgetc(f) == '1';

// Return the file position pointer back to the first character

// fgetc and fputc shift the position pointer by 1 character

fseek(f, -1, SEEK_CUR);

char c = fgetc(f);

// File ended?

while(!feof(f))

{

// Moving back due to fgetc

fseek(f, -1, SEEK_CUR);

// If encrypted - decrypt, decrypted - encrypt

c += is_encrypted ? -1 : 1;

// Overwrite the character that was previously read

// Shift the position pointer forward by one

fputc(c, f);

// Call fseek so we can switch from writing to reading

fseek(f, 0, SEEK_CUR);

// Read the next character, move the position pointer forward

c = fgetc(f);

}

fclose(f);

return 0;

}

File contents:

0Some text to fill the file

And some more textþ

The program will change it like this:

1Tpnf!ufyu!up!gjmm!uif!gjmf

Boe!tpnf!npsf!ufyuÿ

When you restart the program, the file returns to its original form.

If anything, this “encryption” can only protect against a person who is not an IT specialist. In real encryption, each character is encrypted using complex cryptographic algorithms and a long unique secret key (one of them is the RSA algorithm).

So, in this program, I used some functions feof and fseek - what is it?

File navigation

Thanks to the FILE wrapper, we have the ability to navigate through the file by shifting the file position pointer.

Initial position

Each FILE has its own file position indicator, the initial position of which depends on the file mode that we used:

- “r” and “w” – start of file

- “a” – end of file

After that, when reading / writing, the position indicator will move forward by:

- 1 character for fgetc and fputc

- Number of string characters for fgets and fputs

- Number of formatted I/O characters for fscanf and fprintf

- (Size_element * number of_elements) characters for fread and fwrite

Move position

Also, there is a function fseek, which shifts the current position pointer by the specified number of characters, relative to some position.

“Some position” is also indicated by the parameter:

- SEEK_CUR – current position

- SEEK_SET – start of file

- SEEK_END – end of file

// Go back by 1

fseek(f, -1, SEEK_CUR);

// At the beginning

fseek(f, 0, SEEK_SET);

// To the end

fseek(f, 0, SEEK_END);

IMPORTANT: In addition to moving through the file, you must call fseek if you want to switch from read mode to write mode, in combined modes like “r+”, “w+” and “a+”. In the program above, I do this by calling fseek with no offset.

The value of the current position indicator can be obtained through the function ftell

Check that we have reached the end of the file

To check that we have reached the end of the file, we need to call the feof function.

while(!feof(f))

This function returns 1 if the position pointer has reached the end of the file.

feof will only return 1 if we previously called a read function that reached the end of the file (fgetc, fgets, fscanf, fread).

This is due to the fact that the read function, when resting on the end of the file, sets the flag “reached the end of the file”, which the feof function checks.

Also, when calling the read functions, by the return value you can understand that we have reached the end of the file:

- fgetc – will return -1 if the end of the file is reached; instead of -1, in this case, the EOF (End Of File) constant is used

Usually fget returns a character code from 0 to 255

char c = fgetc(f);

if(c == EOF)

// ...

- fgets – will return NULL

char str[100];

if(fgets(str, 100, f) == NULL)

// ...

- fscanf – will return the number of elements read, different from the required (rested at the end of the file)

char str[2];

int x;

int count = fscanf(f, "%c %c %d", str, str+1, &x);

if(count != 3)

// ...

- fread - will return the number of elements read, different from the required one (rested at the end of the file)

char str[100];

int count = fread(str, sizeof(char), 100, f);

if(count != 100)

// ...

Binaries

This is the last topic I want to explain.

The fopen function has another mode of operation - a binary file.

In order to open a file in binary form, you must specify “b” at the end of the line that determines the mode of working with the file:

FILE *f = fopen("some-file.txt", "r+b");

The mode of operation in this case can be any.

What does it change?

Now we are working with a file not as a text, but as a set of bytes.

That is, I can create an int array, write it to a file, and then read from there:

int arr[5] = {1, 2, 4, 8, 16};

FILE *f = fopen("some-file.txt", "wb");

fwrite(arr, sizeof(int), 5, f);

fclose(f);

// Imagine that I'm doing this in another program, for show

int new_arr[5];

f = fopen("some-file.txt", "rb");

fread(new_arr, sizeof(int), 5, f);

fclose(f);

for(int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

printf("%d ", new_arr[i]);

// Program output: 1 2 4 8 16

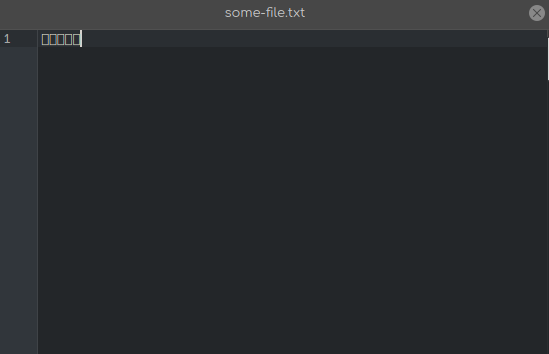

You may think that the file now contains something like “1 2 4 8 16”, but no - there is this:

It looks so weird because the text editor can’t display binary data properly – it’s trying to read character codes.

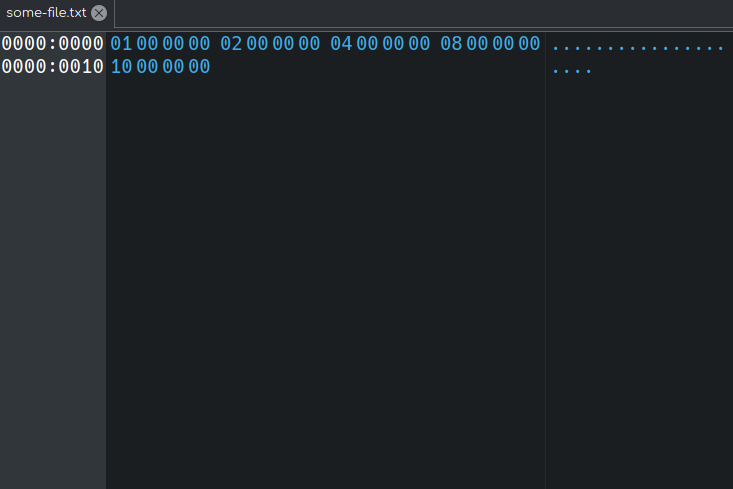

To really find out what lies there, you need to use an editor that can display binary data. Here is how the content looks through such an editor:

They are usually called hex-editors because they display data in hexadecimal notation. Looking at the data in the view of this editor, you can see that our 5 ints are there as if nothing had happened.

Why is it needed at all? Why can’t everything be stored as text?

Imagine that I want to store the unsigned int number 4294967295:

- In a binary file, this number will still take 4 bytes (FF FF FF FF)

- In a text file, this number will take 10 bytes (including 10 characters) + additional load when reading data, since you need to convert the string to unsigned int

About the storage of real numbers, I generally keep quiet

If numerical data in databases were stored in text, then 2+ times more data centers would be needed.

In general, if the user does not need to directly interact with the text in the file, then binary files are a great option.

FAQ

How to work with Russian characters?

We need to add support for Russian localization:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <locale.h>

int main()

{

SetConsoleCP(1251);

SetConsoleOutputCP(1251);

setlocale(LC_ALL, "Rus");

// ...

return 0;

}

And make sure you save the file in “windows 1251” encoding – usually files are saved in UTF-8 encoding. Since UTF-8 encoding is double-byte (each character is encoded with two bytes), you won’t be able to work with them as usual.

How to convert string to number?

Here you can see the documentation for various string-to-number translation functions:

- atoi() – string to int

- atof() – string to double

- atol() – string to long int

The strtof, strtod, strtol and similar functions also convert a string to a number, but have extended functionality - see the documentation.

Reverse conversion is possible through sprintf and fprintf.

Is it possible to remove some symbols/words from the file?

No, you can’t - you can do it in one of two ways:

- Read file into temporary buffer, delete words/characters from buffer and overwrite file with “w” flag with new content

- Create temporary file, read characters/words from source file, write (if character/word matches) to temporary file, at the end remove source file and rename temporary so that it is named as original.

Here is an example of using the first method to solve the problem “remove the word mother from the file”:

FILE *f = fopen("input.txt", "r+");

if(f == NULL)

{

return 0;

}

char buf[1000];

size_t len = fread(buf, sizeof(char), 1000, f);

fclose(f);

// Open with "w" to clean up the file

f = fopen("input.txt", "w");

char *target_word = "mother";

int target_word_len = strlen(target_word);

int target_word_i = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < len; i++)

{

// If the character is not from the keyword

if(buf[i] != target_word[target_word_i])

{

// If before that there were characters included in the key characters -- write to the file

for(int j = target_word_i; j > 0; j--)

fputc(buf[i-j], f);

// Write the current character

fputc(buf[i], f);

target_word_i = 0;

continue;

}

// Increment the character index in the keyword

target_word_i++;

if(target_word_i == target_word_len)

{

// If we reached the last character in the keyword -- reset the index

target_word_i = 0;

}

}

fclose(f);

How to change characters in a file?

Open file in “r+” mode, read, move fseek back a character, write new value.

There is an example in the “Reading/Writing to File” chapter.

Conclusion

In total, you learned what is:

- File

- Descriptor

- Opening a file

- Closing a file

- FILE is a wrapper over a descriptor

- Read and write functions

- Moving the file position pointer

- End of file detection

- Binaries

Congrats, that’s super cool! This is a complex topic, and most likely everything will not settle down in your head at once - try to write a couple of programs, re-read incomprehensible places and relax.

Next are the data structures.